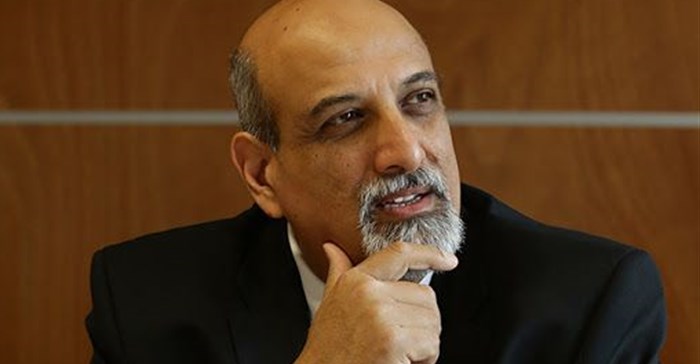

“We probably cannot escape the exponential curve (leading to a rapid increase in cases) but lockdown has bought us time,” the chair of South Africa’s Covid-19 Ministerial Advisory Committee, Professor Salim Abdool Karim, said in a presentation to explain some of the data used by the government to take decisions relating to the epidemic.

He said the data shows that in each country, once there were more than 100 cases the virus spread at a rapid rate with high numbers of new cases being recorded. In these instances hospitals were overwhelmed by patients.

Abdool Karim compared South Africa’s infection rate with the United Kingdom. For the first few weeks the number of new cases in South Africa was virtually the same as in the UK, but from March 26, when lockdown started, the number of cases in South Africa did not continue an upward trajectory, even though those in the UK did.

“In every one of the countries, we looked as the number of cases kept on increasing. There is not a single other country where we have seen this kind of turn,” he added.

Abdool Karim said they had three theories for this phenomenon.

The first was that too few tests were done. The second was that there was not enough testing in the public sector, for patients without medical aid.

He said while testing was restricted at first, there had been an increase in public sector screening since the lockdown. “There has to be a third explanation. Lockdown is about reducing community transmission.”

He explained that the first wave of infections that hit the country was from travellers who brought in the virus from outside. The second wave was those who had contact with the travellers, including the medical personnel who treated them. He said what they didn’t expect was that there was not widespread community transmission.

He said so far rather than one infected person infecting many others, they are only infecting one other person. “That is exactly the reasons for all of our measures – handwashing, social distancing and lockdown – we want each infected person to become a dead-end [for further infections].”

The biggest concern is for the three high-density hubs: Greater Johannesburg, eThekwini and Greater Cape Town. “What we hope for is for the number of new cases steadily declining and disappearing. This is very unlikely though. A more likely scenario is that we stem community transmission. Once we end the lockdown, and we must remember that none of us have immunity against this virus, we are all at risk. That is why as soon as the opportunity arises for this virus to spread we will see the exponential curve again.”

He said while South Africa had become the first country in the world to keep community transmission at a reasonably low level, he thought it was highly unlikely that the country would escape the exponential threat of the virus.

“This virus has a long period of infectiousness. It will spread really fast if people are interacting with one another. We have gained time. We have a unique component to our response: We are going out there and we are proactive – we find the cases before they are coming to the hospital.”

“This coming week is critical. This is when we will see what community transmission of the virus is doing. If these passive cases (patients seeking medical help) is 90 or more on average per day we will have to continue the lockdown. If we see cases fall to between 45 and 89 then we look at active cases (those found by health workers). If these are 1:1,000 or below then we can ease the lockdown.”

Ending the lockdown too abruptly the country would run the risk of undoing the good that was done. “We must plan for a systematic easing – starting with transport hubs and then working our way down.”

The committee’s response to the epidemic would not end with decisions on lockdown. “The next stage, we find the clusters of infections in our communities. I remain concerned over funerals leading to the spread of the virus. We must deal with these issues,” Abdool Karim said.

The next stage was to make sure that the medical response will be as good as it can be when patients start to come to hospital, and ongoing vigilance.

The professor used the metaphor of stopping small flames to prevent a raging fire. “You need people on the ground that are looking for fires. If we see one, we can prevent it. If we get there too late, then we have to put out a raging fire. We are going to try and stay one step ahead of the viral spread. It is a tall order. We are not going to wait for patients to come to hospital.”

He said apart from a hospital surveillance programme he was also thinking about a monthly national surveillance day where small samples of people are tested at schools and big companies.